My Trip to Romania

A Study in Totalitarianism

Chapter One: A Journey into Romania

I was about to step into a world I barely understood—a place where every word could be overheard, and every action watched. It was Mihai’s world, and I was its foreign visitor. Little did I know, the choices I would make in the coming week would echo the risks Mihai had taken years before to escape this same country.

I was once married to a man who had fled Romania in 1976. His story was extraordinary, almost cinematic, but I’ll save the full details for later. I was 18 when I met Mihai. My understanding of the Soviet Union and its satellites came almost entirely from textbooks: restrictions on speech, press, radio, and television; scarcity of food and goods; and the occasional images of bread lines. But textbooks didn’t tell me how people lived every day—under constant watch, constrained yet surviving.

After three years together, I decided to meet Mihai’s family in Romania. I was 21, nervous but determined. In Koblenz, friends helped me prepare. Ion assisted me in booking a “tour” through Neckermann Tours, departing from Hamburg to Constanța. On the plane, I realized I was the only passenger with a blue passport—a small difference that could attract attention I didn’t want.

The airline was Tarom. The plane looked like a secondhand Southwest Airlines jet: faded orange-and-brown upholstery and no passenger comforts. The food was mysterious. On the flight, I met a Lutheran minister traveling to Sibiu. His calm presence and perfect English were comforting. The stewardesses looked exhausted, drained by long hours and scarce resources.

Landing in Constanța, we took a bus to the hotel. Constanța was a cheap seaside destination for Germans, but for me, it felt tense and foreign. At the hotel, the clerk collected all our passports. Visitors weren’t allowed to keep them in Soviet countries. I handed mine over reluctantly, feeling the weight of being both guest and potential threat.

I had also brought a vaccine for the family dog, requiring refrigeration. To ensure it was stored properly, I slipped the clerk a carton of Kent cigarettes as bakshish. My room was small and damp, the smell of mold heavy. Towels were thin, toilet paper crinkly like crepe paper, furniture minimal: a twin bed, one small window, bare walls. I sank onto the bed, the chill seeping into me.

That evening, I walked along the beach. The Black Sea stretched before me, calm and vast. The wind carried salt and seaweed. Instead of peace, I felt isolation, aware of how far I was from home and how different this world was. Tomorrow, Mihai’s mother would arrive to take me to Bucharest, to meet his family—and to step into a past shaped by caution, fear, and resilience.

Mariana picked me up the next morning, and we drove 2.5 hours to Bucharest. The road was two lanes winding through fields and villages. We often stopped for horse-drawn carriages, drivers indifferent to the impatient cars. Miles of burned sunflower fields stretched across the landscape, left unharvested—a quiet act of resistance. The sky was pale, the wind stirring the stalks, whispering of hardship.

Mariana spoke no English, and my French was broken. Somehow, we communicated with her perfect French, my halting attempts, and countless gestures. We laughed over misunderstandings and pointed at passing scenery as if it could explain the world we were driving through.

When we arrived, I met Stefan, Mihai’s father, and Sofia, Mariana’s mother. Their house had belonged to the family, but after World War II, the government seized all private property and divided the house into three apartments. Mihai’s family lived on the second floor of the Bauhaus-designed building.

Inside, the radio and television were always on—a precaution. I was advised never to speak without them, as someone could be listening. It was illegal in the Romania to harbor a foreigner, and I was unmistakably one.

Sofia asked me for Tylenol, lipstick, and jewelry—things I had brought. Western items served as bribes to obtain food, a currency of survival in a flourishing black market economy. Mariana had shopped for two months to serve at least one meat dish per day.

The meat was stringy and tasteless, nothing like what we expected in the West. It might have ended up as pet food in the United States, but I never refused a meal. Gratitude outweighed hesitation.

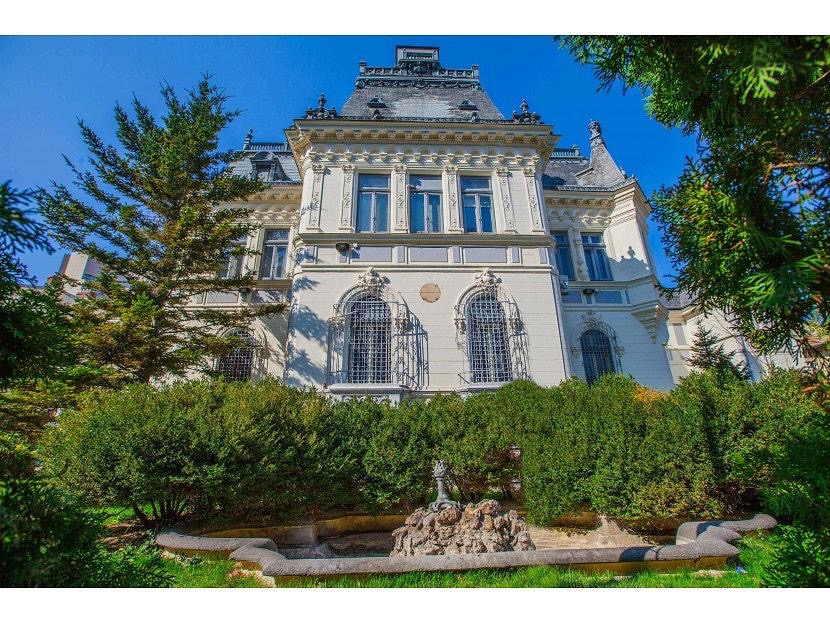

During the week, we took several day trips, though I was forbidden to speak outside the home. One day, we visited the palace of former King Michael I, now the quarters of Nicolae Ceaușescu, President of the Socialist Republic of Romania (a dictator). Armed guards surrounded it, weapons at the ready. Standing there, I felt the weight of the regime—the tension and control permeating every corner of life.

We passed the U.S. Embassy, also heavily guarded. I didn’t have my passport, so I couldn’t enter. Longing and helplessness washed over me—so close to the symbol of my own country, yet completely cut off.

Another day, we traveled to Brașov in Transylvania, ringed by the Carpathians. Medieval villages dotted the countryside, many now tourist attractions. We had a grilled fish meal, fresh and simple, but I remained silent, careful not to speak outside the home.

Finally, the week ended. I packed my bag and items for Mihai: a hand-woven Romanian carpet, an antique mandolin, and letters. I knew it was illegal to take them out, but I carried the mandolin as if it were my own. A risk that may have resulted in my arrest.

At the airport, I saw the Lutheran minister again. We shared coffee while watching other Germans prepare to leave. One man foolishly took pictures inside. Armed guards rushed him, exposing all his film. Shock and fear surged through me, and I worried about the items in my bag.

At customs, the agent didn’t unpack everything. He questioned me about the mandolin, and I said it was mine. Thankfully, he didn’t ask me to play. Relief flooded through me—I had made it through, carrying more than gifts, carrying memories and stories I would never forget.

Chapter Two: Mihai’s Escape

It was Christmas Eve, 1976. Mihai had nothing but wrapped presents—and a plan that could cost land him in prison. He crossed into East Germany and took a train to Denmark, telling passport officials he was visiting family. Luck, timing, and, perhaps carelessness, worked in his favor: the officer had been drinking and didn’t verify his visa.

Denmark held him for thirty days, a temporary sanctuary. Then came the pressure: find a way to West Germany or face deportation. Through a friend, he obtained the necessary visa. From there, he found a sponsor in the U.S.—a Canadian citizen originally from Romania with business in Houston, Texas.

Entry into the United States required him to revoke Romanian citizenship. For ten years, he waited to become a naturalized citizen. Even after arrival, the shadow of his homeland lingered, a reminder of the risks he had taken to reach freedom.

Chapter Three: Reflection

Looking back on my week in Romania, I am struck not only by the courage and resilience I witnessed but also by how vividly it contrasts with the freedoms we are beginning to lose here at home. In America under Trump, I see the erosion of norms I once assumed were unshakable: attacks on the press, the undermining of truth, the dismissal of science, and the steady curtailing of civil liberties. The same vigilance and courage I saw in Mihai’s family—small acts of resistance, careful navigation of rules—feel suddenly necessary here as well.

Mihai escaped Romania to live in a country where freedom was real, even if fragile. Yet today, I watch as rights we took for granted—freedom of speech, the right to protest, access to fair and impartial justice—are challenged, eroded, or dismissed outright. The slow, insidious nature of these losses is striking: like the burned sunflower fields I saw in Romania, resistance and survival require patience, awareness, and courage.

My time in Romania reminded me that liberty is hard-won and easily taken for granted. It is not guaranteed by law alone, but by the choices of citizens, by those willing to speak out, organize, and resist abuses of power. We may not face armed guards or secret police at every corner, but the erosion of institutions, norms, and protections under Trump is a warning: freedom must be actively defended, or it can disappear quietly, one law, one decree, one assault on the truth at a time.

Mihai’s journey, his courage, and his family’s quiet heroism illuminate a path forward for us in America: vigilance, community, and moral courage are essential. The story of his escape and the resilience I witnessed are not just memories—they are a call to action, a reminder that liberty requires constant defense. What we risk losing now is precious, and the time to act is before those freedoms are gone.

https://www.cnn.com/travel/article/ceausescu-trail-bucharest-romania

Looking for More Insights?

Browse our collection of expert articles and guides.